The Mustang Man

Ray Field, Texas’ version of a Horse Whisperer, finds homes for wild ones

By EILEEN McCLELLAND

Copyright 2005 Houston Chronicle

FRANKLIN — Rubio has a wicked, toothy grin and a rakish attitude. He’s a charmer. He better be — he’s going to be a stud when he grows up.

FRANKLIN — Rubio has a wicked, toothy grin and a rakish attitude. He’s a charmer. He better be — he’s going to be a stud when he grows up.

The young mustang’s mother was rescued by the nonprofit RMR Ranch Wild Horse Foundation in Central Texas, where he was born. He playfully carries buckets around a corral and — with his teeth — pulls the hair of his sedate equine peers, trying to interest them in a chase.

“He’s just a baby,” says Jolita “Jo” Tooke, a petite, 20-year-old wild horse wrangler and preveterinary-medicine college student. “He’s like a 10-or11-year-old kid.” Rubio interrupts with a push. “He needs to learn some manners,” she said, with an indulgent smile. “We have shoving matches.”

The comedian Rubio (blond in Spanish) is one of 42 permanent residents — mustangs and burros — Ray Field and his wife, Susan Calhoun, support on their 100-plus-acre ranch in Texas cattle country. Hundreds more mustangs and burros — squeezed out of Western rangelands — have stopped at the ranch before being placed for adoption elsewhere in Texas.

“He promised me a horse ranch when we got married,” Calhoun said. “Be careful what you wish for!”

Field’s promise has turned into a workaholic’s version of a hobby that includes the adoption program, training clinics and rescue work. He lives full-time at the ranch while Calhoun spends weekdays working in Houston and makes the 300-mile round trip to Franklin most weekends.

Franklin is almost due north of Houston, in Robertson County.

After the couple adopted three mustangs from the U.S. Bureau of Land Management about eight years ago, they realized domestic-horse training methods just didn’t work. But they didn’t know where to turn for help.

“We found out that in the state of Texas, a lot of resources were not available to help people who had adopted wild horses,” Calhoun said.

They decided to do what they could to help, drawing on many sources and devising a training method called gentle horsemanship.

Calhoun said Field is an intuitive trainer, seeming to know what the horse is thinking before the horse knows it himself.

His family calls him the Mustang Man.

American icons

For many Americans, the mustang — a descendant of 16th-century Spanish conquistador mounts — is a symbol of the West. At the turn of the 20th century more than 2 million wild horses roamed the plains.

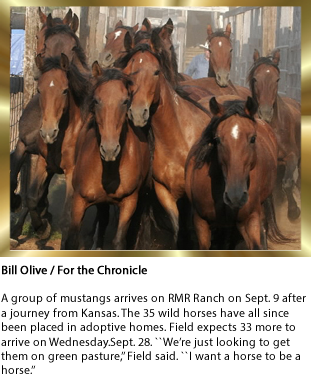

Today, Field estimates there are 53,000 wild mustangs, including 28,000 in federal holding facilities and 25,000 on open range land in 10 Western states. The majority of horses are in Nevada, and most of the burros live in Arizona. By placing 800 to 1,000 mustangs and burros a year, he’s running the largest wild-horse adoption facility, second only to the federal government, which has placed about 200,000 mustangs in homes since 1973.

The BLM charges $125 for adoptions. The Wild Horse Foundation charges an average of $50 per animal, but as much as $250 for specialty horses, such as palominos.

The adoption effort has become more critical this year. The Wild Free-Roaming Horse and Burro Act of 1971 protected the animals from slaughter. But Sen. Conrad Burns, R-Mont., attached an amendment to a spending bill in December 2004 that President Bush signed into law. The amendment allows the sale of older and unwanted wild horses without the safeguards required for adoptions.

After 41 wild horses were killed in an Illinois slaughterhouse in April for human consumption in Europe, the Ford Motor Co. stepped in to save at least another 50 of the animals. And the Bureau of Land Management scrambled to protect the horses, as well, stopping all sales for about a month and then, when sales resumed in May, requiring purchasers to sign a contract stating the mustangs will be treated humanely and won’t be resold for slaughter.

Sales cooled

Tom Pogacnik, California wild horse and burro program manager for the Bureau of Land Management, said these new measures have had a chilling effect on sales while the bureau continues to place horses for adoption.

But Nancy Perry, vice president of government affairs for the Humane Society of the United States, said those motivated by money are able to work around such restrictions. The Humane Society’s position is that slaughtering any horse in the United States should be outlawed by the federal government.

“Any horse sold to anyone at any time becomes vulnerable to being sold to killer-buyers, people hired by the slaughterhouses,” Perry said. “And most people who sell their horses for slaughter don’t even know what they’re doing. They assume they are going to a nice home, and instead they experience a painful and terrifying death all so they can be on a European dinner plate. This is not what Americans want.”

Advocates hope for new legislative protection while Field has gone into adoption overdrive, embroiled in a struggle that has attracted a range of critics, from groups he calls “tree huggers” to skeptical bureaucrats.

“Tree huggers want them turned loose,” he said. “But we’re actually keeping them from being put to death. We can’t just let them go. Texas doesn’t have public land for them.”

A “character”

Pogacnik first worked with the foundation to find new homes for wild burros living in California state parks. The state didn’t want them there, but there was no provision for their adoption. Field placed them in Texas.

In 20 years with the BLM program, Pogacnik hasn’t seen anything like the phenomenon that is Ray Field, a “character” who is both fierce and kind.

He has unlimited patience for horses but can’t abide fools. Field said he once told someone to get off his property because the visitor could not be convinced that Field — wearing his usual shorts, T-shirt, tennis shoes and cap combo — was really the magical horse whisperer he had read about on the Internet and not some ranch hand.

“He’s creating a process that offers a new approach to our adoption program, where he can get the private sector involved,” Pogacnik said. “He may be even pioneering what the future will hold for the adoption program. The hope I have is that he’s going to be able to export that around the country, that it’s not unique to Texas.”

The operation has held up to exacting inspections by the Humane Society and the state of Nevada, Pogacnik said.

Even so, a couple of years ago Field was accused of mistreating horses by a group that posted photos on the Internet. If the mustangs are thin, they arrived that way, he said. As soon as they walk off the trailer, they are fed, given water and plenty of space. In many cases, they are taken to new homes immediately. A veterinarian, who donates her time, is on call.

“He’s got the right personality for it,” Pogacnik said. “He’s been getting whupped on, but he’s proven he can do the job and do it quite well.”

Pogacnik said Field’s no-holds-barred attitude combined with the sensitivity of the wild-horse issue made him some enemies early on.

“Ray has brought discomfort to a lot of people,” Pogacnik said. “He’s made some brash statements that he could do a whole lot more than the BLM. But he’s done it and he’s done it humanely, which is what the public demands. There’s zero tolerance for the animals being injured — or dying. He’s under a lot of scrutiny.”

To Field, the whole thing is just plain common sense. Why not find good Texas homes for mustangs who would otherwise either exist precariously in the wild or in a no-man’s land of governmental bureaucracy and holding facilities? Particularly with the specter of the slaughterhouse looming.

Since mustang advocate Velma Johnson of Nevada, known as Wild Horse Annie, died in 1977, mustang protectors have lost some of their lobbying focus.

“There’s been no united front to protect wild horses,” Field said. “There are a lot of groups out there, but they can’t get their act together. I wanted to get away from the politics of it and put horses first.”

The BLM routinely ships horses and burros to the ranch. They also come from the U.S. Forestry Service, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, the U.S. Navy, the National Park Service and the state of Nevada.

Although Field believes the mustangs’ migration off Western rangeland is in direct response to cattle ranchers’ complaints, Pogacnik said it’s more a question of a scramble for limited resources.

“The perception among the horse organizations is that all the ranchers are anti-horse, but I haven’t seen that,” Pognacnik said. “The vast majority of ranchers just want to keep their populations at a set level.” Years of drought and fire have contributed to the shortage of grazing land as well.

“There is conflict between wild horses and livestock, but there’s also less room for elk, mule deer, big-horned sheep,” Pogacnik said. “All the interests are competing for the same thing. And when you have a very limited resource that doesn’t have much of an opportunity to expand, then you’re going to get conflict.”

Differing opinions

Janet Neal, based in Reno, Nev., is national volunteer and public outreach coordinator for the Bureau of Land Management’s Washington, D.C., office. She said critics are inflamed by the wild-horse issue for myriad reasons.

Janet Neal, based in Reno, Nev., is national volunteer and public outreach coordinator for the Bureau of Land Management’s Washington, D.C., office. She said critics are inflamed by the wild-horse issue for myriad reasons.

“Everyone has a different opinion. Some people want them to stay where they are and let Mother Nature take its course, let the animals die of starvation and dehydration. Some people want all the cattle taken off the land.”

The Wild Horse Foundation is a godsend to the bureau, she said, because maintaining long-term holding facilities are draining the bureau’s already lean budget. It needs help from the private sector. In fiscal 2005, the BLM expects to spend $39.5 million on the wild horse and burro program, including $20.1 million on those in holding facilities.

Family reunion

“It’s just phenomenal what the foundation has been able to do for us as far as placing some of these animals and that the foundation has found good homes for them,” Neal said. “That is the key to all of us. That good homes are found for our animals.”

People who want to help, but can’t take a horse home, can make a monthly donation to name and maintain a horse on the ranch.

Sometimes mustangs are brought to the foundation from private owners, along with a donation to fund their retirement.

Mary Putnam stopped by to visit Dakota, a mustang she adopted in Lake Charles, La., through the BLM and later relinquished to the foundation when she could no longer care for him.

“I drove by and whistled and I saw a head go up,” she told Field when she arrived at the office.

Field drove her to the pasture on a golf cart, where they were quickly surrounded by a small herd looking for edible treats. Dakota was among them.

“I still have your baby pictures,” she told him. She hugged his neck and posed for pictures smiling like a proud mom visiting a college kid.

Putnam said she adopted Dakota almost on a whim. She had the space for him, but no experience with horses.

“It was like bringing home a submarine,” she said. But Dakota somehow became a good friend. “He really was very gentle. He taught me a lot of self-confidence.”

When Putnam left, she wrote a check for $150, at least $100 more than the value of the mugs and T-shirts she bought. Field was grateful. It all adds up.

A Houston business owner, Field relies on adoption fees, donations and the sale of logo souvenirs to keep the operation going.

Each group of horses costs $6,000 to transport. Sometimes the government pays, but sometimes it’s not in the budget and the nonprofit foundation must absorb the cost.

Success stories

The average placement is six horses per adopter, although some ranchers have taken in as many as 30. Others choose one special pet.

Calhoun said the horses are carefully matched with their new owners, who are screened. “We ask a lot of questions,” she said. The average wait for a horse is 30 to 45 days, but some applicants who want certain colors — paints and palominos are popular — are willing to wait longer.

Jim Phillips was mourning a mare when he found the mustang he describes as the love of his life.

“That hurt so bad for a long time,” he said. “I couldn’t pull out of the slump.” Then he saw Lupe, a 6-month-old filly at the Wild Horse Foundation.

“I noticed this one little filly, she had her head down in the hay all the time,” he recalled. “After a while she raised her head and looked right at me, and she had two of the most beautiful eyes you’ve ever seen, and a beautiful head and a short muzzle. And I said, ‘Well, that’s her.’ To make a long story short, she has been the apple of our eye.”

Within a few days, he was able to lead her in a halter. He hopes to saddle-train her when she’s older so his grandchildren and great-grandchildren can ride her.

Now Phillips volunteers to train other young horses for the foundation, although 16-month-old Lupe gets terribly jealous.

“Mustangs seem to have a quick wit to them,” he said. “The mustang will put 110 percent of himself into what he does. They are really alive. Being part Indian myself, I probably understand a little about this thing called freedom. Mustangs are really my kind of horse. I can relate to their feeling of freedom and a little bit of wildness, too.”

Lynn Holleran of College Station said she’s had “various and sundry creatures,” but she always wanted a mustang since she was a little girl. “Don’t ask me why,” she said, “but it’s always been a passion of mine.” On her first scouting expedition, she found Brumby, a golden-hued palomino with three white socks. “He is the gentlest soul,” she said. “How quickly they’re willing to bond with you. It’s magical. If you’re fair with them, they’re willing to work their darndest.”

Medical rescue

While most horses arrive in relatively good shape, Field still is incredulous that he was once shipped a filly that could barely walk. He asked Dr. Ilka Wagner of Hearne to examine the youngster, who arrived during the Christmas season.

Christmas, as she came to be called, had contracted tendons of both front legs.

“My heart went out to that filly,” Wagner said. “If she could tough out a trailer ride from Nevada in that condition, we owed it to her to give it a shot and try surgery. Sometimes it doesn’t work, but I hated to put her down without trying.”

Wagner not only operated but she also took the filly home. “I was going to adopt one of the mustangs, anyway,” she said. “So I adopted one that needs some after-care. She’ll never make a riding horse, but she runs around out in the pasture.”

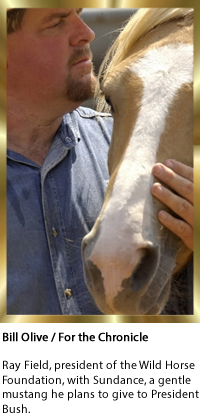

To draw attention to the cause, Field has made a gift of the mustang Sundance to President Bush. Formerly abused, Sundance is a medium-size horse who likes men and hides from women. Field hopes Bush will claim Sundance when he leaves office.

“I thought they’d look well together,” Field said. “Sundance has an elegant glow about him.”

Contact the foundation 979-828-3927 or on the web for more information, www.wildhorsefoundation.org